The most remarkable feature of this historical moment on Earth is not that we are on the way to destroying the world — we’ve actually been on the way for quite a while. It is that we are beginning to wake up, as from a millennia-long sleep, to a whole new relationship to our world, to ourselves and each other…The Great Turning is a name for the essential adventure of our time: the shift from the industrial growth society to a life-sustaining civilization. Joanna Macy In Coming Back to Life.

It takes a certain amount of chutzpah to think this big, but I am haunted by a dream of the earth flourishing, healing from the many wounds we know only too well. I believe that to achieve a turnaround to a sustainable civilization will require a shift of human consciousness. I believe that a key component of this shift is that we each must be able to see ourselves as members of a living Earth community, above and beyond our identification with self, tribe, nation, etc. The good news is, I believe this shift is not too far beyond our grasp.

My flirtation with global thinking probably started one night as a 10 year old lying in my bed in the little house across the street from Poinsettia Playground in West Hollywood. Maybe we had been studying the solar system in fourth grade that day, and I was trying to remember what was outside of the outer planet. I took it step by step to the limits of the known universe. But, when I started asking myself what was outside of that outer limit — something broke open. A vast spaciousness opened up, and I found myself in awe, wondering ‘what there was’ before there was anything, and before there was nothing. The sense of vastness and mystery has haunted me ever since. It was too silly or embarrassing to talk about with friends or family at the time. It makes you too vulnerable, too flaky and weird. I feel safer sharing about it now, 57 years later.

The next hint was in fifth grade, when we moved to a new little tract home in the San Fernando Valley. All the walls between all the backyards had just been built. One night in a dream all the backyard walls disappeared. It became one large spacious valley, with people free to move around in the easily shared space, a vision of the living earth, free from artificial human boundaries. I felt really good about this, but it didn’t make sense to bring it up in conversation at the time.

I became a seeker of sorts, always trying to transcend culturally imposed limits. Which brought me to Big Sur, age 21, taking LSD sitting on a bluff at Esalen with a spectacular view straight down into the ocean swirling around the rocks. The part of my personality that had always watched and commented on experience from a safe distance dissolved without a trace, leaving me directly and intimately in contact with, and at one with, the great earth and all of life.

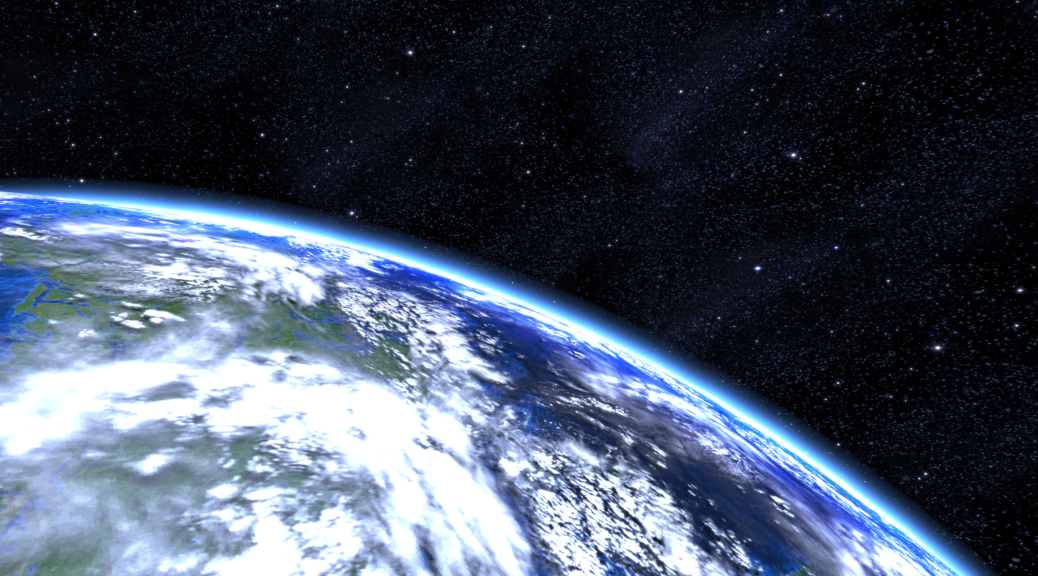

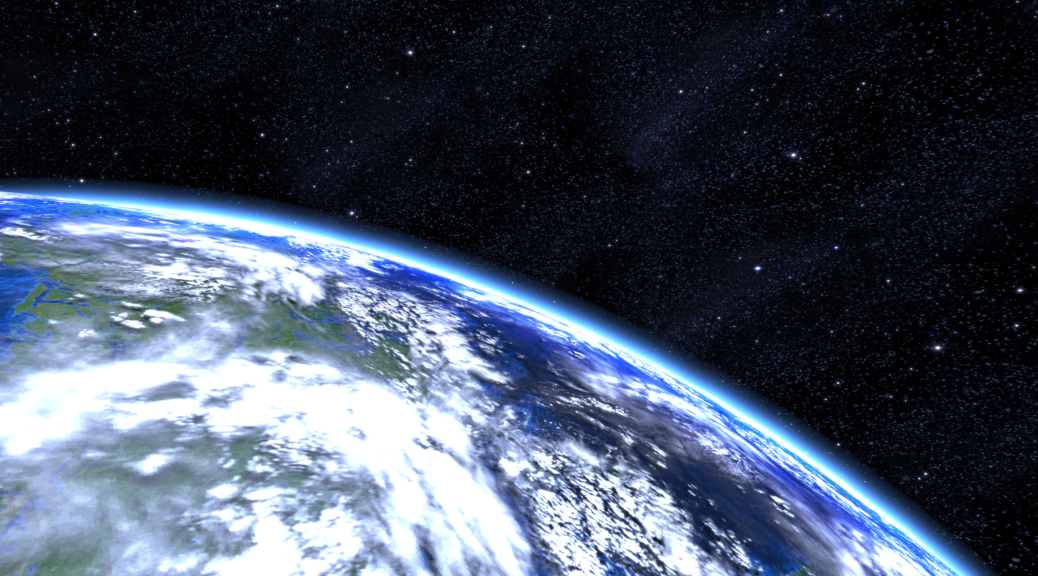

When I got back to the Stanford campus a few days later, I ran into Stewart Brand, who was walking around giving away buttons that said, “Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole Earth yet?” It was 1965, I was in the process of dropping out to join the emerging counterculture, and the first photo of the Earth didn’t appear until December 1968. When it did, my sense of vast interior spaciousness and possibility was linked to a visual image that felt familiar and important. Brand put the photo on the cover of his Whole Earth Catalog, and a significant part of my generation began to explore the many implications of the new vision it produced. Very soon after I was living on a thousand acre farming commune, out to save the world.

Practicality intervened. I was not ready to be an obedient follower of the guru on the Farm. I was lonely there and unable to establish a satisfying relationship. I had lived with virtually no money, and no means of earning any, for the six years since I dropped out of college. I needed to recalibrate to survive and flourish. I dragged my worn out body and mind back to my parents’ house and got a job as a TV stagehand.

Ever the seeker, within a month I moved to the Zen Center of Los Angeles, but I kept working as a stagehand while beginning to practice daily meditation. At the Zen Center we trained in zazen and the way of the Bodhisattva, who vows not to attain liberation until all beings are brought to liberation. But at work, as a new stagehand, I was on the destruction crew. While our more experienced counterparts were in the big shop, building scenery for the day’s TV shows, our job was to tear apart and fill the dumpsters with the elaborate sets used the previous day, made with precious woods from all over the world. One day standing on top of one of these mountains of fresh scrap I had a vision of how my work fit in with the life and energy flows of the Earth. Morally shaken, I wanted to do something about it. I enrolled in the new major they had just created at UCLA, Geography/Ecosystems, with a goal of eventually becoming an environmental lawyer. After a successful quarter I had to consider that I would still have to finish a BA before applying to law school, and that the law really wasn’t my passion. But I was determined to find a right livelihood that would support my development as a practitioner committed to the Bodhisattva path. I did some work toward becoming a psychotherapist, and then spent 13 years as a corporate manager, with all the attendant ethical qualms.

The experiences of Earth awareness were vivid but intermittent. For many years, immersed in my corporate work and institutional Zen practice, I lost touch with a sense of global perspective. [9/20/2019 – Distracted by spiritual materialism, I somehow didn’t connect the boundless experience of zazen with ecological awareness.] It came back big time when I saw the film “An Inconvenient Truth” in 2006, which made some of the connections between the idyllic looking ball in space and the mayhem we have been perpetrating upon it for the last 100-200 years. I was inspired by the film to look for more resources that might help me understand how to participate in reversing the destructive trend.

Somehow I found a book called The Dream of the Earth by cultural historian Thomas Berry. I was totally entranced. He seemed to be a visionary who went to the depths of the issue, with a voice of intelligence, wisdom and passion, seamlessly integrating science, religion, history, poetry and prophecy. (Did I say I was impressed?) Berry was not talking about technology adjustments to deal with climate change. His theme was the accelerating degradation of all living systems, including the most massive wave of species extinctions since the age of the dinosaurs. All the previous great extinctions had been caused by geologic shifts. But guess what was causing this one — a wave of extinctions caused by a species of (not quite fully) conscious beings. One quote to illustrate the time horizon of Berry’s analysis:

“Our own special role, which we will hand on to our children, is that of managing the arduous transition from the terminal Cenozoic to the emerging Ecozoic era, the period when humans will be present to the planet as participating members of the comprehensive Earth community…Earth as a biospiritual planet must become for us the basic referent in identifying our own future”.

I looked up Cenozoic and found out is the most recent 65 million years, the period of life as we know it, sometimes called the Age of Mammals. He says the geologic era will end in our time or soon after if the assault on nature continues, or transition to a new geologic age of flourishing earth/human partnership if we succeed at “The Great Work of Our Time.”

The image of the ball in space edged toward the center of my web of priorities. But, again, what about practicality? Joanna Macy says there are three dimensions necessary for us to achieve the Great Turning (her name for the Great Work):

1. Actions to slow the damage to Earth and its beings.

2. Analysis of structural causes and the creation of structural alternatives.

3. Shift in Consciousness.

For better or worse, my passion is for the shift of consciousness. It’s what I have really been working on all my life. I am now retired, collecting pensions from my careers as a corporate manager and as a school librarian. I will continue to keep serving on the board of my homeowners association, and doing all the practical things I have to do. But I will also keep seeking out and refining my role in the global rite of passage that we are all going through, whether we like it or not. I will continue to open myself to the dream of the Earth Community and share the dream as I am able. My own secret weapon in this whole enterprise is cultivating a sense of humor about it all, to keep from getting bogged down in the potential grimness, despair, cynicism, or anger. I fortunately have a very healthy and active inner Trickster who is always challenging the Bodhisattva to lighten up and back off for a while. He says, “Don’t push it. Give people space to find their own way. Give it a break”. I’ve decided it’s usually best to let the Trickster have the last word.

Working toward a shared planetary consciousness that heals the Earth