Written for my 1997 Memoir Class

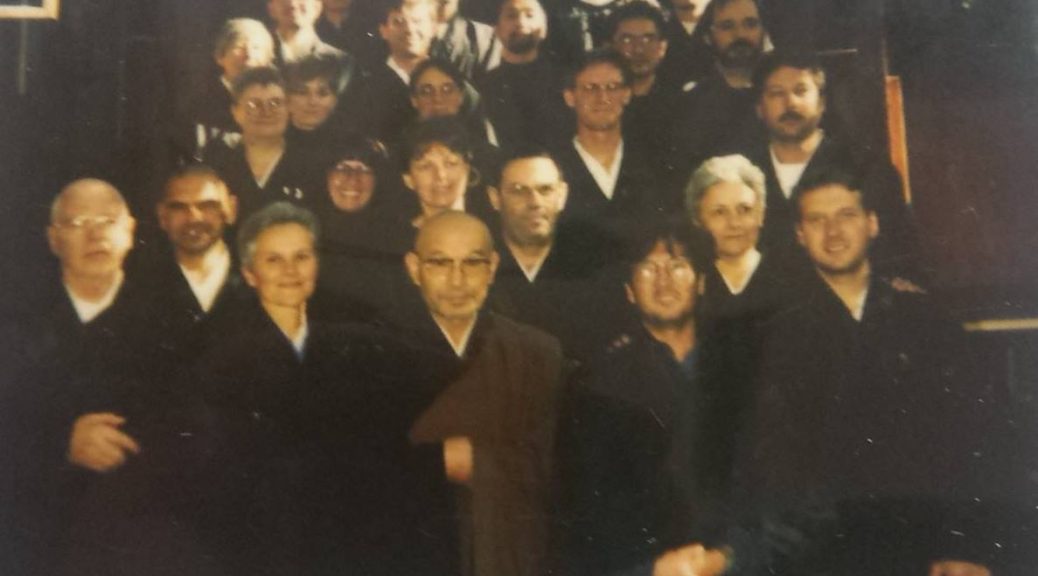

Linked from Taizan Maezumi Roshi, Zen Center of Los Angeles and Spiritual Steppingstones August 8, 2008

My teacher, Taizan Maezumi Roshi, died in Japan on Mothers’ Day, 1995. That morning, because Roshi was in Japan, I was giving the private interviews upstairs in the Founders’ Room at Zen Center of Los Angeles. At one point during the morning I had a strange experience of feeling time totally stand still. I made a mental note that this sensation was unusual for its depth and clarity, and how “long” it seemed to last. That’s possibly the moment Roshi died, which we later heard was about 10am Los Angeles time.

After morning sitting, my wife and daughter and I participated in the lovely Mothers’ Day gathering at the Center in the morning, and then went off to have brunch in the Valley with my parents. When we arrived back home, late in the afternoon, I saw two people walking toward me, wearing their sitting robes. It was Richard and Patricia, but there was no reason to be wearing robes that late in the afternoon. The Sunday schedule ended at noon. I had a feeling of foreboding as they walked toward us. Maybe I could see the expressions on their faces. Richard spoke first, in his usual blunt manner, but more softly than usual. “Roshi died this morning in Japan. He died in his sleep. They think it was a heart attack.”

My thought was “What? You’re kidding.” But I couldn’t speak. I just listened.

“We’re going to be doing a memorial service in a few minutes. You’re supposed to run it. Here’s the outline of what to include.”

“How do you know this? Where did you hear this?”

“Tenshin called us from Mountain Center. Roshi’s wife called Mountain Center and told them.”

I went into the house, stunned, to change into my robes so I could put together the service quickly. There was a message waiting on the answering machine. It was Tenshin, with the same story Richard had told. Also, he said I should find my copy of the instructions for the emergency Succession procedure, and fax it to two of the local Dharma Successors.

So now I’d heard it from two sources. Apparently this was real. But from the outset there was no chance to reflect, because as the Director of Ceremonies it was my responsibility to put together the first quick memorial service, and then to organize many of the activities immediately afterward. A couple of months later, to help with the transition, I became the Chief Administrator for the next two years. Now that I am finally relieved of that responsibility, two and a half years after the death, I can finally begin to reflect on the magnitude of this relationship, and where my life goes next.

The first time I saw Maezumi Roshi, in September of 1972, it was the culmination of ten years of reading, searching, and fantasizing about a Zen Master. I had read “The Way of Zen” by Alan Watts in high school, in 1962, and was completely enchanted by his depiction of the Zen Master as the paradoxical, rascally embodiment of freedom, wisdom, and independence. The fantasy was reinforced by reading Kerouac’s “On the Road” shortly thereafter, with his frequent reference to ‘Zen Lunatics’. They were characters Kerouac modeled on Han Shan and Shih-te, semi-legendary Chinese hermit poets depicted in brush paintings sneaking into the kitchen of the Zen Monastery, stealing food, and laughing hysterically, never to be caught in the act. I found and loved the poems of Han Shan, Cold Mountain, that were translated into English by Gary Snyder. Snyder was the model for Kerouac’s Japhy Ryder, the one member of the core beat circle who went to Japan and studied in a Zen monastery. These were the first early influences that set me off on a meandering trail to try to find a real live Zen Master.

In 1969 I made a first shift from theory to practice, with beginners instruction at the Berkeley Zendo. I sat a few times with Suzuki Roshi in San Francisco and Chino Sensei in Santa Cruz, but still had enough playing left to do in the counter-culture that I wasn’t able to settle down. Then finally, on September 7, 1972, I came to hear a talk at Zen Center of Los Angeles.

That first evening at the Zen Center, seeing and hearing Maezumi Roshi, was like coming home. This is what I had been looking for and thinking I might never find. This man radiated the depth, mastery, warmth, freedom, seriousness, and playfulness that I had only imagined. But he was real. And there he was. In his late thirties, physically small, but projecting a compact intensity, he was a dignified presence sitting cross-legged in his robes on the raised platform at the front of the room. Through a very thick accent, his English revealed subtlety and mastery both in the precision of its insight, and the seemingly artless imprecision of its strangely apt errors of syntax. The impish humor, with absolutely no sense of self-consciousness, was irresistible.

Roshi had been speaking on Thursday evenings on a classic text called Genjo Koan. The section for tonight was:

When a fish swims in the ocean, there is no limit to the water, no matter how far it swims.

When a bird flies in the sky, there is no limit to the air, no matter how far it flies.

Thus, no creature ever comes short of its own completeness.

Wherever it stands, it does not fail to cover the ground…

Know, then, that water is life.

Know that air is life.

The bird is life and the fish is life.

Life is the bird and life is the fish.

The impression the evening made on me was stunning. It wasn’t just his mastery of the text, and what he brought to it, although that was part of it. Being in the midst of the seamless ritual, the light aroma of the Japanese pine stick incense, and Roshi’s warm presence, everything told me loud and clear this is where I should be. The next morning I came back and rented an apartment across the street, and my entire life since that day, a quarter of a century, has been lived in and around the Center.

Three years after that first evening I took vows as a Buddhist. Maezumi Roshi, whose name was Taizan, Great Mountain, gave me the name Kenzan Mokunin, Firm Mountain, Silent Patience. The irony was beautiful. When I arrived I was a scattered ex- hippie, barely able to concentrate on anything. For the first few years almost the only instruction he had for me was “I want you to settle down”. And settle I did. Within a few more years I was married, raising a family, working as a manager in a large corporation, sitting on the Board of Directors of the Zen Center. I became that firm mountain on almost every level. I felt daily gratitude for my good fortune in having found this great teacher who helped me find myself, my own strengths, working toward my own independence.

Nineteen years after that first meeting, and four years before his sudden, unexpected death, Roshi asked four of us, in 1991, to start giving the formal private interviews to students whenever he was away traveling. It had been a topic of discussion around the Center for some time, that with Roshi traveling so much, and since all of his successors had left the Center to start their own places, new students coming in were not getting enough guidance. He set up a new category, Senior Instructor, and asked us to begin to teach.

We were not being made formal Dharma Successors. None of us had yet completed one of the prerequisites to being authorized as a Sensei, which was completion of the koan curriculum. A koan can be any deep question to which you bring the full force of your life energy, to penetrate and clarify with the entire body and mind. The traditional koans are cases, often dialogs, depicting the enlightenment experiences or key teachings of ancient masters. The student must penetrate the true meaning of each case, and then present it to the teacher in private interview as one’s own living experience. There are hundreds of these cases, in several volumes, that had to be presented and approved. Here’s an example, “Rinzai’s ‘True Man’”:

Rinzai said to the assembly, “There is a true man with no rank always going out and in through the portals of your face. Beginners who have not yet witnessed it, look! Look!

Then a monk came forward and said, “What is the true man of no rank?”

Rinzai got down from the seat, grabbed and held him: the monk hesitated. Rinzai pushed him away and said, “The true man of no rank–what a dried shit stick he is!”