Written for my 1976 B.A. Portfolio for Antioch.

1. Describe the learning setting. Include where it took place, the role of other persons who were involved with you, and any materials and methods employed which assisted your learning.

This is the one learning activity that spans the entire program. All the time I was in college, in bands in San Francisco, on the Farm in Tennessee, and studying Zen and therapy in Los Angeles, I have been reading on my own. I have compiled a bibliography of about one hundred and fifty books and articles I have read on the subjects of oriental religion and western psychology.

Other persons involved include gurus that I have sought out over this period, and fellow seekers who have suggested books. The libraries and bookstores in whatever town I happened to be in during this period have provided the materials. The basic method has been to read whatever seemed to speak to the level of development at which I found myself at any given time.

2. Describe your participation and responsibilities in this setting.

Only the most recent of this reading was done with Antioch in mind. For instance, I carried a copy of Gurdjieff to all the concerts my band played in Berkeley in 1969, to finish reading his big book which I started while working in the oil refinery in 1965. I’ve never taken a course where I was asked to read Freud, or Jung, or Reich, and yet I have read thousands of pages by and about them. I have felt a responsibility to myself to explore myself and psychology and religion. Since I was looking for answers about my own life, the responsibilities were self-imposed, or self-discovered, or self-created.

3. Describe new skills and/or knowledge derived from this learning activity which contribute to your Degree Plan.

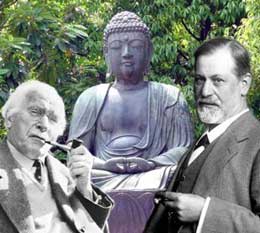

My knowledge of psychology can be described under six main headings: 1) Freudian, 2) Reichian and Bio-Energetic, 3) Jungian, 4) Behaviorist, 5) Humanistic-Maslowian, and 6) Communication-theory oriented.

1. Freudian. I have knowledge of Freudian psychology from reading “Psychopathology of Everyday Life,” “Civilization and Its Discontents,” “Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego,” and Calvin Hall’s “Primer of Freudian Psychology.” In studying child care I have read works of men strongly influenced by Freud: “Childhood and Society” by Eric Erickson and “Love Is Not Enough,” by Bruno Bettelheim.

2. Reichian and Bio-Energetic. I became interested in the work of one of Freud’s early students, Wilhelm Reich, who emphasized the sexual drive from which he felt Freud had turned away. Reich’s work which has influenced me includes “The Function of the Orgasm,” “Listen Little Man,” and “Reich Speaks Out on Freud.” “Man in the Trap,” by Ellsworth Baker, a student of Reich’s, is an introduction to Reichian ideas on character structure.

The founders of Gestalt and Bio-Energetics have been strongly influenced by Reich, especially in paying attention to the flow of energy in the body. In addition to Reading Perls’s “Ego, Hunger, and Aggression,” and “Gestalt Therapy,” I was able to have personal contact with him on a social basis and at his dream seminar. While in bio-energetic therapy with Dick Westfall in Los Angeles I read “The Betrayal of the Body” and “Pleasure,” by Alexander Lowen, the founder of bioenergetic analysis. From Perls I learned to keep a keen eye on what is happening in the present moment. From Bioenergetics I learned how it feels when the body is pushed to its limits and comes up against physical blocks to growth. I also read and learned some breathing and movement techniques for working through these blocks. Reichian work is documented under its own heading.

3. Jungian. My reading in Jung includes “The Essential Jung,” edited byJoseph Campbell, and “Psyche, Symbol, and Archetype,” by Aniella Jaffe, which is a survey of the range of Jung’s work. I also found the Jungian approach in “Psychic Energy” by Mary Esther Harding, where she describes the process of psychotherapy as like an alchemical experiment, needing a sealed vessel to produce the gold. Joseph Campbell’s works on mythology, including “Myths to Live By” and “The Hero With a Thousand Faces,” overlap with and dramatize the realm of the Jungian archetypes. I have learned to see the great myths as metaphors for what we do with our lives, and vice versa.

4. Behaviorist. The only contact I have with behaviorism is from a brief time in Psych 1 at UCLA, where I read Skinner’s “Walden Two,” and some time in Psych 1 at Cal State LA, where I saw films of Dr. Delgado’s bulls with brain implants. The ethical problems brought up by trying to operate in an ethical vacuum make me think the whole thing is a waste of time. I’ll have to learn the positive aspects of behaviorism someday. I mention it only because it is what has kept me from studying psychology in a regular college.

5. Humanistic. From the so-called Third Force, or humanistic psychology I have read Carl Rogers’s “On Becoming a Person,” and works by Abraham Maslow, including “Religion, Values, and Peak Experiences.” Just before enrolling at Antioch I started reading Maslow’s “Toward a Psychology of Being,” and “Farther Reaches of Human Nature.” Maslow’s approach teaches me that there is room in an expanded science of psychology to study the healthiest and highest states of consciousness. I also found an existentialist-humanistic viewpoint in Clark Moustakas’s “Loneliness” and “The Child’s Discovery of Himself.”

6. Communication-theory. There is a school of psychology dealing with human problems from the viewpoint of information theory. I found this in “Steps to an Ecology of Mind” by Gregory Bateson and “Therapeutic Communication” by Jurgen Ruesch. The model allows for a study of transactions on the intrapersonal, interpersonal, cultural, and planetary levels all using the same metaphor. There is a strong tendency to abstract too much and thus lose the human quality of what we do, however.

In the field of Buddhism, my primary interest has been Zen. I started in high school by reading Alan Watts’s “The Way of Zen,” and a little later Eugen Herrigel’s “Zen in the Art of Archery.” I have studied translations of and commentaries on koans in “The Zen Koan,” by Miura and Sasaki, “Zen Flesh, Zen Bones,” by Reps and Senzaki, and Shibayama Roshi’s “Zen Comments on the Mumonkan.”

I read books by the first generation of Zen monks in America: “Zen for Americans,” by Soyen Shaku, “Buddhism and Zen,” by Nyogen Senzaki, and the series of “Essays in Zen,” by D.T. Suzuki. I have studied the available translations of the Mahayana sutras in English, including the Diamond Sutra, Platform, Lotus, Avatamsaka, and Surangama. Although actual practice with Maezumi Roshi has taught me more of the experience of Zen, I still consider the literature a valuable asset, but primarily as an inspiration for practice.

I have read a number of books on Tibetan Buddhism. In general, the Tibetan flavor tends to be a bit more colorful and diverse, while the Zen tends to be a bit austere and formal. This colorful approach can be seen especially in the works of contemporary lama Chogyam Trungpa, as I found in his “Born in Tibet,” “Meditation in Action,” “Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism,” and “The Dawn of Tantra,” as well as attendance at his three-day seminar in Los Angeles last year on the subject of “The Tantric Yanas.” Somewhat more formal in the Zen sense is the work of Tarthang Tulku Rinpoche. I have read “Calm and Clear,” translated under his auspices, and “Crystal Mirror,” numbers 1-4, his annual publication. I also had the pleasure of being received in personal interviews when he first came to America in 1970. He is now editing a series of books and teaching courses designed for psychology professionals, and is one of the strongest voices from the east offering insights into our psychology.

Other Tibetan sources include biographies of Milarepa and Naropa, Herbert Guenther’s works “Treasures on the Tibetan Middle Way” and “The Tantric Way of Life,” and the works of Lama Anagarika Govinda, “The Way of the White Clouds” and “Foundations of Tibetan Mysticism.” This has all been for perspective on the Buddhist range of teachings, for as a Zen student it is not necessary or advisable to also follow the practices of another teaching lineage. I have learned from my study of this second of many areas of Buddhism that at least these two both point to the experience of Shakyamuni Buddha, and both encourage us to realize this state in our own lives.

Some works I have read which attempt to discuss both the eastern and western psychological traditions include the pioneering “Cosmic Consciousness,” by R.M. Bucke, in which he gives examples of a long series of religious geniuses who attained this “cosmic consciousness,” usually between thirty and thirty-five years of age. Aldous Huxley’s “The Perennial Philosophy” draws parallels from all the world’s mystical traditions. Claudio Naranjo, in “The One Quest” and his half of “The Psychology of Meditation,” discusses this unified mystical tradition in terms of the Western psychological concepts of attention and awareness. “Reflections of Mind,” edited by Tarthang Tulku, gives the first responses of psychology professionals to the three month workshop he offers for them every summer.

4. Self-Assessment: Evaluate this learning activity. Mention such things as the quality of the experience itself and its personal significance to you.

I will try to express the personal significance of this learning by following the reading chronologically, rather than subject by subject, and commenting on how it related to my personal development as we go along. I was not reading randomly, or in a vacuum. Only now, looking back on thirteen years of reading and searching, can I begin to discern a developmental story line. I will follow this story line in terms of the interplay of theory and practice. Obviously psychology and religion are responses to the need to make sense out of human experience, theories that grow from practice. But sometimes these theories themselves become inspiration for action, and then practice follows theory.

Probably my psychological reading started when I began to notice my overactive mental processes. I can remember being fourteen or fifteen years old and thinking about thinking about thinking. I needed some theories to bring coherence into a chaotic mental field, and I needed to find a field of action in which to apply all of this mental activity.

In 1962, before I started college, I had done a book report on a young people’s biography of Sigmund Freud. I was very impressed at the way the author presented the AHA! Experience of Freud deciding he wanted to be a psychiatrist. I wished my choice of career could be that clear cut and exciting, and secretly hoped I could be a psychiatrist because it had worked so well for Freud.

There was a copy of “Psychopathology of Everyday Life” on the shelf at home and a chance to start on the path. My life had been so intellectual and repressed I could easily relate to eruptions from the unconscious into the politeness of everyday life. Also in my reading that last year before college was “Growing Up Absurd” by Paul Goodman, and “Existentialism from Dostoevsky to Sartre” edited by Walter Kaufmann. So I was reading about an absurd existence, with materials rudely popping up from the realms which are being ignored or repressed.

That same year I read “The Aims of Education” by Alfred North Whitehead, recommended for freshmen entering Stanford, and was excited by the Appolonian scholarly ferment presented. And that same year I read “The Way of Zen” by Alan Watts and “On the Road” by Jack Kerouac. Both pointed to a free undisciplined existence deriving from something called Zen, and revolving around a hero who could do anything, called the Zen master, or Zen lunatic.

My experience was intellectual and repressed, as confirmed by reading the existentialists and Goodman. There was a range of solutions offered in theory. One was to deepen the intellectual commitment, as suggested by Whitehead. A second was to examine the manifestations of the repressed material, as suggested by Freud. This became the seed for a career idea I am nurturing with this program. A third was to act out on the impulse to break out of the trap, as suggested by Kerouac. I tried this for a few years and found it to be a sterile dead-end for me. A fourth possibility was the discipline of Zen, suggested by Watts. In this degree program I am still working with the main metaphors of Zen and Therapy, referring to the Bohemian experiment as part of my past, and re-entering the intellectual life having brought in all these enriching elements.

After a year at Stanford, and the first disillusionment with my ability to cope in the academic world, I was taking drum lessons and reading “Zen in the Art of Archery” for relaxation. The idea was to become mindless and therefore highly skilled in the practice of my drumming. Here was a way to begin to apply the theory of Zen to the practice of my life, to break out of the narrow intellectual style.

In 1964 I was back at Stanford for another try, reading “On Becoming a Person” by Carl Rogers, and “The Function of the Orgasm” by Wilhelm Reich. I was beginning to try to make an integration bringing in emotive levels and not just the shallow intellectual attempts of the freshman year. I was also finding an attractive image in the butterfly dream of Chuang-Tzu in my Chinese Philosophy course. The koans of “Zen Flesh, Zen Bones,” from which I would read in the bookstore, provided glimpses of clarity. Psychedelics were in the air and I was reading Watts, Leary, and Huxley on the subject.

I was beginning to polarize between drumming, Zen, and psychedelics representing the free life and school representing repression. I attempted to bridge the gap with Chinese Philosophy in school and some independent reading in humanistic psychology. In 1965 I read Norman O. Brown’s “Life Against Death,” in which the polarity I had been dealing with was drawn to the breaking point, around a theme of totally overcoming repression. I read Freud’s “Civilization and Its Discontents,” on which Brown had based much of his argument. It seems that if you took Freud seriously, the task was to overcome repression so as to be able to transcend society, which was necessarily a system of repressions. And from the feeling in the air at Stanford in 1965 the instant cure for a repressed unconscious was LSD.

Norman Brown’s book was a strong influence toward giving up the attempt to integrate, and choosing the feeling side. Marcuse’s “Eros and Civilization” had the same influence, and I acted out what I took to be their advice. Here is an instance of theory influencing practice. Just as I should have been creating a personality from the conscious elements at hand, I decided to blast the whole system and flood myself with unconscious material via LSD. I was reading “The Next Development in Man” by Lancelot Law Whyte, about an emerging unification of consciousness. I was reading Campbell’s “Hero With a Thousand Faces” preparing to experience all of them in the heroic quest into the ocean of the unconscious.

For me Campbell’s book was not just a theory about archetypes. I took it as a guide to my own inner experience. Whyte’s book was not just intellectual history, but a guide to unifying my own divided personality.

After meeting Norman Brown, Ken Kesey, and Richard Alpert around the Stanford campus, I took LSD at Big Sur and spent that first evening at a Fritz Perls dream seminar. Back in Palo Alto I combed the library shelves for someone who could speak to the experience in which I became one with the ocean. Only the “Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch” rang like a clear bell, where Hui-Neng spoke of “vast emptiness” as the ultimate reality. Later that year I was reading “Ego, Hunger, and Aggression” by Perls, having been impressed by him on that first trip, and trying to begin to digest the huge chunk of experience I had bitten off.

Now my experience seemed rich and the theories seemed thin. Gestalt and Zen were the only theories that came close to my experience, but even they seemed pale. I entered a period in which life jumped far ahead of reading.

In 1966 I almost literally floated around the Bay Area, attending the first “be-in,” and reading Maslow’s “Religion, Values, and Peak Experiences,” Bucke’s “Cosmic Consciousness,” and some works of Meher Baba. I needed validation that this oceanic sense which was still pervasive could be a viable point of view from which to approach society. Unfortunately, I had no skill in the relative, only in the realm of the absolute, and so I found myself a rock drummer in San Francisco.

In 1967 the only book I read was by the Sufi Hazrat Inayat Khan on the mystical language of music. That year I played for tens of thousands of people in the park and forty-thousand on top of Mount Tamalpais. I hit upon amplified music to express the overwhelming cosmic sense. My only contact with theory was the validation I found in the Sufi book about the cosmic aspect of music.

By 1968 the magic was wearing off and I found myself in a band of amphetamine addicts in Los Angeles. I joined some old friends in Berkeley in 1969, and began to comb the mystical literature for a path I could enter which would help me sustain the high, which was by now becoming difficult. I read “The Master Game,” “In Search of the Miraculous,” “Teachings of Don Juan,” and found a teacher in Stephen Gaskin. The only western psychological literature I read that year in Berkeley was Perls, Hefferline, and Goodman’s “Gestalt Therapy,” a series of exercises designed to stir up the boundary between the individual and the world.

As the LSD experience began to wear thin I felt a strong need for direction from reading. Stephen provided a link between drugs and a path, between practice and theory. I was trying all sorts of theories to regain a sense of contact and path.

I also read “Three Pillars of Zen” that year, 1969, and began to sit zazen at the Berkeley zendo. The review of “Three Pillars” in the San Francisco Oracle was the first indication I had that there was a way to practice Zen here in twentieth century America. It was quite a wonderful revelation. That year I sat with Suzuki Roshi three times in San Francisco, although I never heard him speak. Now here was a spiritual discipline, a unity of theory and practice. It is still the central metaphor in my life.

In 1970 I was still studying with Steve Gaskin. The band had moved to Santa Cruz to be in the country. I didn’t read any psychological literature that year. I was reading “Be Here Now” by Baba Ram Dass, “Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind” by Suzuki Roshi, and a lot of books on Tibetan Buddhism. Although I was becoming more involved with the theory of Buddhism, I was not completely ready for the practice with a teacher. I was studying with a dope teacher who was influenced by Buddhism. My practice was about half way into Zen, my reading a little more than half way.

I spent the year of 1971 on the Caravan and Farm with Stephen mostly reading the “Diamond Sutra” and “Ch’an and Zen Teachings” edited by Charles Luk. When I decided to leave the farm in December I went to my tent, read the “Diamond Sutra” all the way through, and left. When I arrived in Los Angeles I read “Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego” by Freud, which described the primal horde and the tyranny and murder of the primal father. It all felt like the Farm, everything but the murder, but I could feel it rising to the surface in me, and went back wanting to let everyone know what Freud had said about what we were doing. Once in that atmosphere it was laughable to try to talk that way and I left again, knowing that phase of my life was over.

Now my reading was completely into Zen, but the practice was lagging. I finally broke away from Stephen, and found a critique of my former practice in Freud. Here psychological theory had a critical function, providing insight into the cause of my unhappiness. The object of the criticism couldn’t hear the criticism, so I left over the issue of the authoritarian father-leader.

In 1972 I had resettled in Los Angeles and was working as a stagehand. I had no psychological interests. I had been reading “Layman P’ang” in Florida, imagining the road was my zendo. Then before coming to the Zen Center I was toying with the idea of going north to study with Tarthang Tulku Rimpoche, and was reading the “Crystal Mirror” and the “Biography of Naropa.” I was also looking back at the Farm and reading the “Caravan,” “The Alternative,” and “The Perennial Philosophy,” one of Stephen’s favorite books. Finally in August of 1972 I got a job as a stagehand, and in September moved to the Zen Center.

In this year I completed the transition, making the move to the Zen Center, where I still live. I spent some time looking forward to a Zen practice while I was still on the road, and some time looking back on the positive aspects of where I had been, but the decisive move was made.

In 1973 all my reading was on the experience of Zen practice, i.e. “Primer of Soto Zen,” “The Zen Koan,” “Hara,” by Durkheim, and Flora Courtois’s “An Experience of Enlightenment.” I had been reading all the Don Juan books as they came out, and this year it was “Journey to Ixtlan,” in which he began to see the drugs were not the core of the teaching, they were only a finger pointing to the moon. I began to fully appreciate the harmony of theory and practice in Zen. I felt affirmation from Castaneda that drugs were not the core of the practice.

As I settled and began looking for a woman, the one I was with felt so bad about what I was doing that she suggested I go into therapy rather than try to work it out on her. In May I went into therapy with Pat Sutton. By June of 1973 I had tired of being a stagehand and was seriously thinking of studying for a career as a psychotherapist. I started working at Ingleside Mental Health Center. While there I read “Childhood and Society” by Erickson, “Therapeutic Communication” by Ruesch, and “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden” by Hannah Green. I had a brief time in bio-energetics, at which time I read a couple of books by Lowen. I had a brief time in Reichian work, at which time I read “Me and the Orgone” by Orson Bean. I had a brief time in Psych 1 at UCLA, at which time I read “Walden II.” I was still practicing Zen and reading the works of the first Zen monks in the west, Nyogen Senzaki, DT Suzuki, and Soyen Shaku. In November I transferred from Ingleside to Hathaway. It was a year in which I began to take psychology seriously, primarily because Pat Sutton was the first psychologist I could take seriously. At the same time I was getting deeper into the theory and practice of Zen.

By 1975 I was again going back to school in psychology. I tried a couple of weeks at Cal State LA, where I read the “Primer of Freudian Psychology.” In my practice as a child care worker, and from being in therapy, I was making contact with the child, externally and internally. I studied child development to further round out this experience. This was an example of self-directed reading to further professional and personal goals in a particular area, that of child development and child care.

I read “The Essential Jung” and began to understand the nature of the quest I had begun when I took LSD and purposely flooded myself with unconscious material. I had forgotten or not been conscious of the fact that the original motivation was to have a fuller range of material with which to build a personality. Only now did I perceive a pattern beginning to emerge. I could feel myself maturing and coming into my own power. I remembered trying to understand Jung on individuation years earlier. I now felt more prepared to understand his theories about the process of maturation. Here was an example of experience leading to a deeper understanding by being supplemented and shaped by psychological theory.

Other elements with which I was dealing just before enrollment at Antioch included Reichian work, and transpersonal psychology. I read Reich’s book on Freud, and “Man in the Trap” by Reich’s student Ellsworth Baker, and went back into Reichian therapy when I actually enrolled. I started subscribing to the “Journal for Transpersonal Psychology.” Here I found the psychology of LSD and meditation discussed seriously. Three main aspects of my life were beginning to mature: the religious, the career, and the sexual. My practical and theoretical grasp of Zen continued to deepen. My decision to become a psychotherapist continued to strengthen, and with it the need to find a sufficiently integrative format. My long-time sexual repressedness still represented a barrier to full maturity and I concentrated on this in the Reichian work. The integration of all these strands on the practical and theoretical levels is what I have come to deal with in this program.

At present it seems that all of this reading and exploring has brought me to a point where I will continue toward becoming a psychotherapist, tapping into and being informed by the practice of Zen. While training to be a therapist I will be working through my own sexual maturation. I will probably work toward a master’s degree in social work, because it will offer me the most job flexibility and versatility of the paths realistically available. Reichian work, psychedelic research, and transpersonal psychology are three possible areas of special interest that I might pursue within that context. The shift from drugs to Zen discipline, and then to psychotherapy informed by Zen is the major dynamic movement through this period of time. This development represents a richness of theory and practice on which I hope to be able to draw in the future. I hope I have shown how theory and practice have informed each other in the working out of this personal development, and the personal significance for me of the reading I have done.

5. Describe the methods of evaluation and feedback used during the learning experience itself.

The feedback has come from gurus and friends and my own personal development. Only with this program have I looked at the reading itself closely enough to extract a pattern.

6. Describe the material products of this learning experience, if any.

Bibliography.

7. List the forms of testimony and evaluation that you will include in your portfolio as demonstrable evidence of learning. Please attach these.

Evaluation by Ron Sharrin based on this write-up and oral communication.

—